Contents:

Haemophilus Influenzae: Classification, Identification, Infection, and Resistance

◉ Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae is a Gram-negative bacterium that has long been a formidable pathogen, especially in children. Although it was initially identified as the presumed cause of influenza (hence its name "influenzae"), it is now recognized as a major agent of respiratory and invasive infections, such as meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis. Thanks to vaccination, the incidence of H. influenzae type b (Hib) infections has significantly decreased, but non-typeable strains (NTHi) remain a major concern, particularly in adults with chronic lung diseases or immunocompromised conditions.

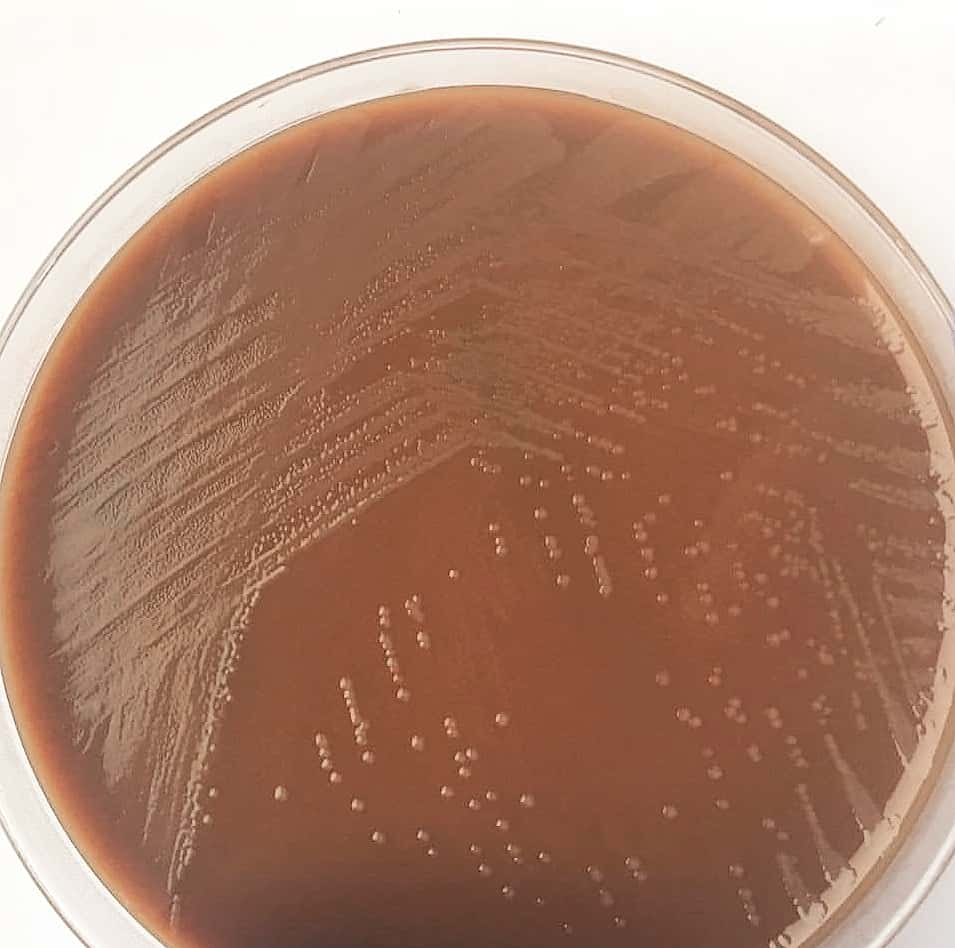

Photo 01: Colonies of Haemophilus influenzae

◉ Origin of the Name: Haemophilus influenzae

The name Haemophilus influenzae is rich in meaning, reflecting both its biological properties and its history.

Haemophilus:

- The term "Haemophilus" comes from the Greek words "haema" (blood) and "philos" (loving), meaning "blood-loving." This name refers to the bacterium's essential need for growth factors present in blood: factor X (hemin) and factor V (NAD or NADP). These factors are indispensable for its growth and survival.

Influenzae:

- The name "influenzae" was given by Richard Pfeiffer in 1892 when he isolated the bacterium from patients with influenza. At the time, it was mistakenly believed that this bacterium was the cause of influenza (in Italian, "influenza" means "influence," referring to the supposed influence of the stars on this disease). Although this hypothesis has been disproven, the name has remained.

◉ Classification and Nomenclature

Haemophilus influenzae belongs to the genus Haemophilus, which includes 16 species, within the family Pasteurellaceae. H. influenzae is the type species of the genus and is distinguished by its need for specific growth factors.

- Family: Pasteurellaceae

- Genus: Haemophilus

- Type species: H. influenzae

Strains of H. influenzae are classified into two main categories: encapsulated (typeable) strains and non-encapsulated (non-typeable, NTHi) strains. Encapsulated strains are serotyped into six groups (a to f) based on their polyribitol phosphate capsule.

◉ Epidemiology

Haemophilus influenzae normally colonizes the upper respiratory tract of humans. Before the introduction of the conjugate vaccine, H. influenzae type b (Hib) was the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in children under 5 years old, with a carriage rate of 2-4%. Thanks to vaccination, this rate is now less than 1%. However, non-typeable strains (NTHi) colonize 50-80% of the population and are responsible for recurrent respiratory infections in adults.

Transmission of H. influenzae occurs primarily through direct contact with respiratory secretions. Invasive infections, such as meningitis or septicemia, occur when the bacterium crosses the respiratory mucosa and enters the bloodstream. Encapsulated strains, particularly type b, can resist phagocytosis due to their capsule, allowing them to spread to other organs.

◉ Pathogenesis

Haemophilus influenzae is an opportunistic pathogen that causes infections by exploiting weaknesses in the host's defenses. Its ability to cause disease depends on several virulence factors, the most important of which are its capsule and adhesins.

- Capsule: Encapsulated (typeable) strains possess a polyribitol phosphate capsule that protects them from phagocytosis, enabling invasive infections such as meningitis and septicemia.

- Adhesins: Non-encapsulated (non-typeable, NTHi) strains adhere to respiratory mucosa through surface proteins (Hia, Hap), causing localized infections such as otitis media and sinusitis.

- Biofilms: The formation of biofilms protects the bacterium from immune defenses and antibiotics, promoting chronic infections.

- Immune Evasion: H. influenzae produces proteases that degrade secretory IgA, neutralizing part of the local immune response.

◉ Diseases

Haemophilus influenzae was once the leading cause of meningitis in children, but the introduction of the conjugate vaccine has reduced the incidence of this disease by more than 90%. Today, H. influenzae remains a significant cause of respiratory infections, including:

- In children: Otitis media, sinusitis, conjunctivitis, epiglottitis.

- In adults: Pneumonia, COPD exacerbations, nosocomial infections.

Non-typeable strains (NTHi) are particularly concerning in immunocompromised adults or those with chronic lung diseases.

◉ Morphology and Identification

◉ A. Morphology

- In clinical samples from acute infections, Haemophilus influenzae appears as small Gram-negative bacilli (1.5 μm), often observed in pairs or short chains.

- In culture, its morphology varies depending on the medium and incubation time:

- After 6-8 hours in a rich medium, cocco-bacillary forms predominate, while longer and pleomorphic forms appear over time.

- Young cultures (6-18 hours) exhibit a well-defined capsule, essential for serotyping and bacterial virulence.

◉ B. Culture and Growth

- H. influenzae grows on chocolate agar enriched with IsoVitaleX, forming flat, grayish-brown colonies 1-2 mm in diameter after 24 hours of incubation.

- Growth requires the presence of two essential factors: factor X (hemin) and factor V (NAD).

- On sheep blood agar, the bacterium can grow near staphylococcal colonies, a phenomenon called "satellite phenomenon," due to the release of NAD by staphylococci.

◉ C. Identification

Identification of H. influenzae relies on:

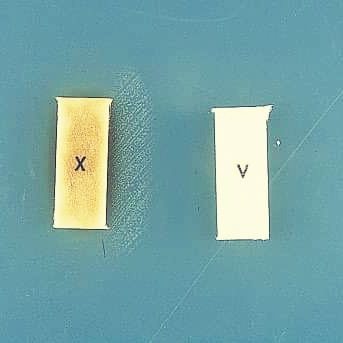

- Requirements for factors X and V: Specific tests, such as satellite growth or the use of strips containing these factors, confirm these requirements.

- Serotyping: Based on capsular polysaccharides, it distinguishes typeable (a to f) from non-typeable (NTHi) strains.

- Biotyping: Strains can be classified into eight biotypes based on their production of indole, ornithine decarboxylase, and urease. Biotypes I and II are most frequently associated with invasive infections.

◉ Laboratory Diagnostic Tests

The diagnosis of Haemophilus influenzae relies on several methods, adapted to the type of infection and available samples (CSF, pus, blood, etc.):

- Gram staining: Observation of small Gram-negative bacilli in clinical samples (sputum, cerebrospinal fluid, blood).

- Culture: Isolation on chocolate agar enriched with IsoVitaleX. Colonies appear flat and grayish-brown after 24 hours of incubation. The "satellite phenomenon" on sheep blood agar confirms the need for factor V.

- Biochemical tests: Identification of requirements for factors X (hemin) and V (NAD) to confirm the genus Haemophilus.

- Molecular techniques: Real-time PCR allows rapid detection of H. influenzae and its antibiotic resistance genes (e.g., blaTEM for beta-lactamases).

- Antigen detection: Immunological tests to detect capsular antigens in cerebrospinal fluid are less commonly used due to their low sensitivity.

Technique: When cultured on Mueller-Hinton agar, which lacks factors X and V, H. influenzae only grows between strips impregnated with factors X and V. The factors diffuse into the medium, and colonies are observed in areas where the concentration of each factor is conducive to growth.

◉ Antibiotic sensitivity

Haemophilus influenzae exhibits antibiotic resistance that can be intrinsic or acquired, requiring susceptibility testing to guide treatment.

◉ 1- Intrinsic Resistance

- Ineffective antibiotics: 16-membered macrolides, lincosamides, glycopeptides.

- Moderate susceptibility: 14-15-membered macrolides (erythromycin), first-generation cephalosporins.

◉ 2- Acquired Resistance

- Beta-lactams: Resistance is often due to the production of beta-lactamases (e.g., TEM type) or mutations in penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs). Beta-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., clavulanic acid) restore antibiotic efficacy.

- Other antibiotics: Rare but possible resistance to tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Note: Precautions must be taken when preparing inoculum concentrations (0.5 McFarland) for Haemophilus spp., especially for beta-lactamase-producing strains of H. influenzae, as higher suspensions may lead to falsely resistant results.

◉ Conclusion

Haemophilus influenzae remains an important pathogen despite advances in vaccination. Non-typeable strains (NTHi) and antibiotic resistance represent major public health challenges. Efforts are needed to develop new vaccines targeting non-typeable strains and to monitor the emergence of antibiotic resistance. A better understanding of virulence and resistance mechanisms will pave the way for new therapeutic strategies.